ارثنگ (Arthang)

تاریخ هنر (گزیدۀ 'گفتارها، یادداشتهای پراکنده، مقاله و پژوهشها)

ارثنگ (Arthang)

تاریخ هنر (گزیدۀ 'گفتارها، یادداشتهای پراکنده، مقاله و پژوهشها)بیستون یا طاق بستان؟ سرچشمههای بازنمایی صخرهنگارۀ فرهاد در سنت خمسهنگاری با نگاه به گزارشهای سدههای آغازین اسلامی

مقالۀ «بیستون یا طاق بستان؟ سرچشمههای بازنمایی صخرهنگارۀ فرهاد در سنت خمسهنگاری با نگاه به گزارشهای سدههای آغازین اسلامی» در نشریۀ رهپویۀ حکمت هنر منتشر شد.

نویسنده: مریم کشمیری، استادیار گروه نقاشی دانشگاه الزهرا

رهپویۀ حکمت هنر، دورۀ ۳، شمارۀ ۱، شماره پیاپی ۴، شهریور ۱۴۰۳، صفحات ۶۷ تا ۸۴.

چکیده:

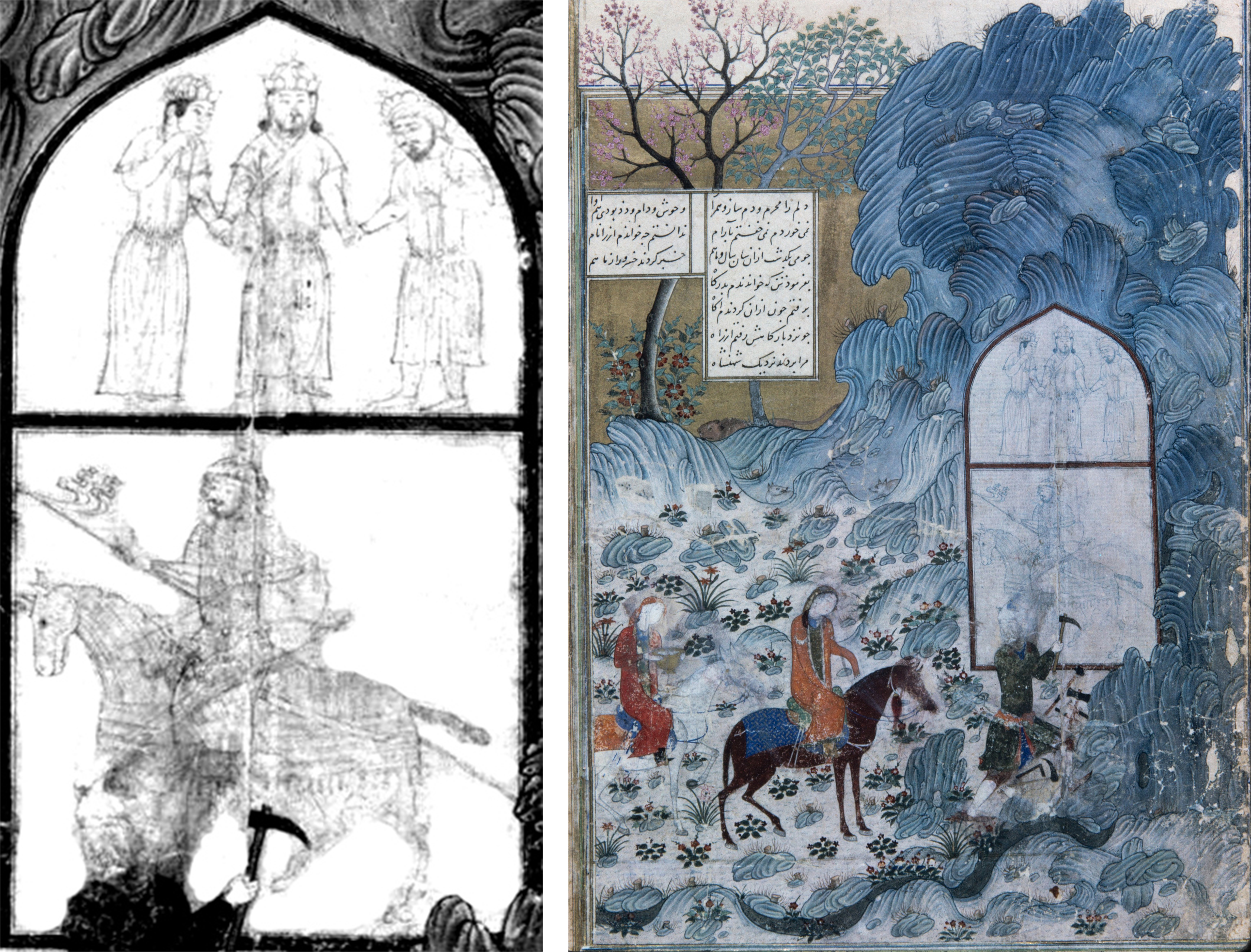

در بسیاری از نگارههای خسرو و شیرین خمسۀ نظامی که فرازهایی از حضور فرهاد در کوهستان را نمایش میدهند، نقش صخرهنگارۀ فرهاد بر کوه بیستون نیز به تصویر درآمده است. نظامی این صخرهنگاره را «صورت شیرین» و «شکل شاه و شبدیز» معرفی میکند که به دستور خسروپرویز، با تیشۀ استادانۀ فرهاد بر بیستون کنده میشود. نگارگران بر پایۀ این یادآوری، بیش از دو سده سنتی را در ساختوپرداخت خمسههای مصور تکرار کردهاند که در چشم بینندۀ امروز، پرسشبرانگیز است: باآنکه خسرو، فرهاد را راهی بیستون میکند، نگارگران نقوش ایوان بزرگ طاقبستان را بر کوه مینگارند. پژوهش حاضر، نگاهی تاریخی دارد و به شیوۀ توصیفی ـ تحلیلی، بر بنیان 20 نگاره از 47 نسخۀ مصور (خمسه نظامی) در پی دریافت چرایی جانشینی نقشها در نگارههاست. از بازخوانی ریزبینانۀ گزارشهای دورۀ اسلامی چنین برمیآید که جابهجایی تصویری نقشها در نگارههای ایرانی، نه از سر اشتباه و درآمیزی دو مکان تاریخی، بلکه پیامدِ گزینش آگاهانۀ نگارگران بوده است. در گذشته، ناآشنایی با هویت و مفهوم نقشبرجستههای بیستون، بهویژه نقش داریوش، در کنارِ ظرفیتهای نقوش ایوان بزرگ در هماهنگی با حافظۀ تاریخی ـ روایی آن روزگار، این جانشینی را برای نگارنده و نگرنده پذیرفتنی میساخت.از مهمترین ظرفیتهای نقوش ایوان بزرگ میتوان به نمایش چهرۀ زنانه، نقش اسب، شکوه شهریاری، و همبستگی آن با فرازهای زندگی خسروپرویز اشاره کرد.

واژگان کلیدی:

بیستون، خسرو و شیرین، خمسهنگاری، طاق بستان، فرهاد کوهکن، نقشبرجستههای کرمانشاهان

مقاله را در وبسایت نشریه در اینجا ببینید.

اصل مقاله را از اینجا دریافت کنید.

Bistun or Taq-i Bostan? The Roots of Farhad's Bas-Relief Representation in Illustrated Khamsas (Quintet) with a Focus on Early Islamic Writings

Maryam Keshmiri

Assistant Professor, Department of Painting, Faculty of Art, Alzahra University

Abstract

The story of Ḵosrow and Shīrīn is a romantic tale composed by Neẓāmī

Ganjavī in the 12th century, though its roots go back centuries earlier.

In this story, Shīrīn is an Armenian princess renowned for her

extraordinary beauty. Ḵosrow is none other than Ḵosrow II Parvēz (r.

591-628), the powerful Sassanian king, who falls in love with Shīrīn and

desires to marry her. Neẓāmī introduces a fictional character whose

historical identity is unknown: Farhād, a master craftsman skilled in

rock carving and mountain reliefs. In Neẓāmī’s tale, Farhād falls in

love with Shīrīn. Enraged by this rival, Ḵosrow sends Farhād to the

mountains under the pretext of carving Mount Bīstūn. Bīstūn is a

mountain near modern-day Kermānšāh, Iran, renowned for its exquisite

historical bas-reliefs, including Darius the Great’s inscription and the

statue of Hercules from the Seleucid era. Neẓāmī references this

mountain in his story, portraying Farhād as the creator of these

reliefs.

The illustration of the Ḵhosrow and Shīrīn story in the Ḵamsa(Quintet) manuscripts

was particularly popular between the late 14th and late 16th centuries.

Workshops in important cities such as Tabriz, Shiraz, and Herat

produced these manuscripts under the patronage of Iranian kings and

princes. Among the scenes illustrated in these manuscripts, the

depictions of Farhād’s encounters with Shīrīn were particularly

prominent and frequently illustrated. Notable examples include the scene

where Shīrīn visits Farhād or the moment when Farhād carries Shīrīn and

her horse on his shoulders to the palace. In many of these illustrated Ḵamsas(Quintet),

when artists painted these scenes, they also included Farhād’s

bas-relief on the mountain. Neẓāmī describes this bas-relief as “the

portrait of Shīrīn” and “the figure of the king and Shabdiz” on Mount

Bīstūn in Kermānšāh. Shabdiz was the name of Ḵosrow Parvēz’s famous

horse, whose remarkable qualities have been praised in many ancient

texts. It’s written that Ḵhosrow loved this horse so dearly that upon

its death, he commanded its image be carved into the mountain.

However, a curious detail arises: the artists who illustrated these

scenes over several centuries, whenever they wished to depict the

bas-relief of Mount Bīstūn, instead painted a different relief— one, now

known as Taq-i Bostān. The bas-relief at Taq-i Bostān, located in a

large rock-cut arch, is several kilometers from Bīstūn. This research

addresses the question: Why did this substitution occur in Persian

painting: Why did the artists depict Taq-i Bostān instead of Bīstūn? Did

they not recognize the difference between the two sites, or did they

lack an accurate understanding of the reliefs?

In search of answers, ancient reports about these two locations were

first examined to understand the historical perception of these sites.

The study reveals that none of the earlier reports from the 8th to 15th

centuries confused the artworks of Bīstūn and Taq-i Bostān. These

reports were likely the source of knowledge for later artists.

Therefore, if no confusion existed in earlier observations and accounts,

why did Persian painters choose to depict the reliefs of the grand arch

at Taq-i Bostān instead of those at Bīstūn?

For this research, 20 paintings from 47 illustrated Ḵamsa(Quintet)

manuscripts were examined and analyzed. The findings indicate that the

visual substitution of these reliefs in Persian paintings was a

deliberate artistic choice, not a result of confusion between the two

historical sites. The ancient people’s unfamiliarity with the meaning

and historical identity of Bīstūn’s bas-reliefs, particularly the

figures represented, led them to choose the imagery of Taq-i Bostān. The

motifs of Taq-i Bostān were more understandable and relatable when

viewed in the context of Ḵhosrow’s life. It seems that the reliefs of

Taq-i Bostān had significant narrative potential for the people of that

time, allowing them to associate these images with familiar oral

stories. Some of the core elements of this narrative potential include

the depiction of a female figure, the horse motif, the grandeur of

Sassanian kingship, and their connection to Ḵhosrow’s life. These

features were precisely the elements needed for illustrating Neẓāmī’s

story of Ḵosrow and Shīrīn: the depiction of a woman (Shīrīn), the image

of a horse (Shabdiz), a wealthy and powerful king (the Sasanian king

Ḵosrow II Parvēz), who can remove his rival, and, most importantly,

bas-reliefs carved into a mountain, representing Farhād’s craftsmanship.

Key Words

Nezami Ganjavi, Khamsa (Quintet), Khosrow and Shirin, Farhad, Bas-reliefs of Kermanshahan, Bistun, Taq-i Bostan

See article, here.